Saturday, December 16, 2017

Star Wars movie review--but not the one you expect

I've been working on a series of blog posts on Brad Gregory's The Unintended Reformation, which was published five years ago and which I finished reading about a year ago. So it probably shouldn't surprise that I am now writing not about the new Star Wars (which I'm going to see on Tuesday) but the last one, which I only just watched last night (in preparation for seeing the new one). I'd heard a lot of mixed reports on it--many of my friends think that it's too much of a rehash of previous films. Having watched it, I think that's true. It's not a shattering, ground-breaking movie, but I enjoyed it a lot (and probably would have been more impressed on the large screen). I'm certainly looking forward to watching the next one.

Like many people, I particularly liked the story of Finn, the stormtrooper who changes sides. He begins the story without a name except the designation FN-2187. Early in the film, one of his comrades is killed, and reaches up and touches FN-2187 on the helmet, leaving a bloodstained handprint. At this point we only know the character as just another faceless stormtrooper, but the bloodstain individualizes him. A few minutes later, he and he alone refuses to massacre civilians, and eventually helps a Resistance pilot escape. In the fighter, as they are fleeing the "First Order," the pilot, Poe Dameron, names FN-2187 "Finn," just before the fighter crashes and Finn believes that Dameron is dead. I wasn't sure that Dameron would stay dead, and of course he doesn't--turns out he was thrown from the craft and survived perfectly fine. Apparently the original plan was for him to die, and I think that would have made Finn's journey from nameless stormtrooper to individualized hero more poignant.

I also really liked the ending, in which Rey finally tracks Luke Skywalker down on a coastline that reminded me vividly of my ancestral Shetland (i believe it's actually Skellig Michael in Ireland). As I said to someone today, I can put up with nearly anything in a movie that gives me a shot of a windswept landscape overlooking the North Atlantic.

The curse of Star Wars, I think, is Joseph Campbell. His homogenized stereotype of a "hero's journey" has locked the franchise into certain patterns that it can't seem to escape. Of course Hollywood blockbusters tend to follow well-worn grooves anyway, but the particular mythic model George Lucas chose has, I think, accentuated that basic tendency of commercial entertainment. This is why George R. R. Martin's work stands out, I think. It isn't so much that Martin is "cynical" or "nihilistic" (though of course his vision is very dark), but that he treats his characters as individuals. Their actions fall into certain broad patterns, but the complexity and freedom of real human lives keeps busting the heroic stereotypes apart.

Supposedly the new Star Wars movie is bolder than its predecessor. I'll find out on Tuesday. But since apparently it starts with more shots of Skellig Michael, I'll be happy no matter what.

Sunday, December 10, 2017

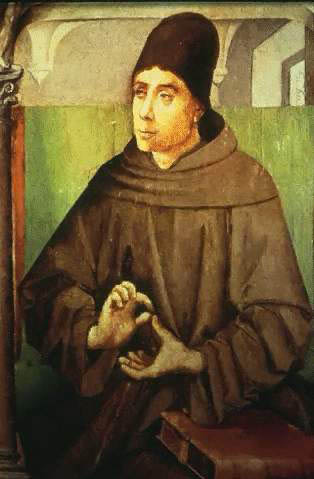

Brad Gregory--Excluding God, or, It's all the fault of Duns Scotus

(image: public domain)

Chapter One of The Unintended Reformation is probably the most often cited. Indeed, many of the negative reactions to the book focus on the thesis Gregory argues here. Ironically, the chapter is atypical inasmuch as the root of modern secularism identified here lies not in the Reformation itself but in late medieval theology, specifically the work of Duns Scotus. According to Gregory, Scotus' concept of "univocity" radically altered the traditional Christian understanding of God. In traditional Christian theology (i.e., in the work of the Church Fathers, the Eastern tradition, or the earlier scholastics such as Aquinas), God is radically other than creation. All creation depends on God and participates in God, but no concept drawn from creation (as all our concepts are) is adequate to describe God. God is not a specific example of a broader category of "things that exist." God transcends all our categories and all our language. For Aquinas--himself much less "apophatic" (i.e., more willing to make positive claims about God) than many other great theologians of the tradition--even "being" can only be predicated of creatures and God analogously. Creaturely "being" derives from God's and thus has something that resembles it, but the differences are always going to be far greater than the similarities.

Scotus, in contrast, believes that there is a concept of "being" that can be univocally applied to God and creatures. Gregory argues that this is, implicitly, a radical move that makes it possible to think and speak about God in the same way we do about creation. But he admits that in itself this highly abstruse theory would have had little effect. This is where the Reformation comes in. By shattering the unity of Western Christendom and igniting fierce debates about how we know God's revelation, the Reformation cast Europeans back on an abstract, philosophical concept of God, which had been subtly altered by Scotus. Hence, post-Reformation Christians (both Catholic and Protestant) increasingly tended to think of God as the greatest of beings within a universe that could in principle be explained through reason and natural law. As the rapidly developing disciplines of the natural sciences explained more and more of reality without reference to God, God's place within this cosmos dwindled to that of the First Cause of Deism, and eventually to Feuerbach's mere projection of the human mind.

There is a reason why this sweeping argument has drawn so much criticism. In the first place, it's generally a bad idea to rest big claims about intellectual history on Scotus if you aren't a Scotus expert, because Scotus is such a darn difficult author. (In fact, I have a paper on Calvin I have wanted to publish for years which, among other revisions, probably needs to have all the Scotus cut out.) While Scotus did say that one can predicate being univocally of God and creatures, this was a very narrow and technical point, and the people I know who know something about Scotus generally seem to agree that it won't bear the weight Gregory puts on it. While Gregory does cite Scotus scholarship, he generally doesn't seem to be familiar with the bulk of recent work on Scotus, or at least he doesn't cite that work. Instead, his view seems to owe a lot to a 20th-century Catholic polemical trope of blaming the Reformation on the distortions of late medieval theology. In the 1990s, the largely Anglican theological movement called "Radical Orthodoxy" embraced the idea that Scotus had been the point where the Western theological tradition Went Wrong, and many more broadly "post-liberal" theologians of different traditions make similar points, it seems to me. Gregory cites Fr. (now Bishop) Robert Barron's 2007 The Priority of Christ for his view on the significance of Scotus' adoption of the concept of the univocity of being. Now I myself am very sympathetic to this strand of recent theology. I think there may be something to the "blame Scotus" argument, in fact. But it's unwise to rest too much weight on these claims when generally speaking the people who are actual Scotus experts qualify them at best and scoff at them at worst.

Furthermore, the idea that post-Scotus theologians, including the Protestant Reformers, thought of God as fundamentally the same kind of being we are seems very strange. William Ockham, seen by many (including Gregory) as taking Scotus' innovations even further, had a radically "apophatic" view of God in which God's nature is pretty much completely unknowable and all we can talk about is God's will. And this is generally the approach of the Reformers. Calvin, contrary to the stereotype many hold of him, fulminates against the idea that God is arbitrary, to the point of rejecting the basic distinction all medieval theologians made between what God has chosen to do and what God could have done but didn't. (I write about this in that paper I referred to earlier.) He believes that all God's actions flow from his nature. But the nature, again, is fundamentally unknowable. The older Catholic polemical trope of blaming everything on the late medieval scholastics, in fact, was more likely to argue that Ockham in particular made God so entirely other from us that reason has nothing to say about God--and this is certainly a more plausible interpretation of at least some of the early Protestant theologians (most notably Luther).

But even if Gregory is all out to sea on what he says about Scotus, and wrong to suggest that the Reformers followed Scotus in this respect, that doesn't really affect the basic argument of the chapter, at least insofar as it supports the overall case made by the book. After all, blaming Scotus wouldn't, in itself, support Gregory's argument that the Reformation is the source of the modern secular world. Rather, Gregory's most significant argument is that the sharp disagreements about God's acts of revelation that took place in the Reformation left post-Reformation Christians with no sure ground to speak about God except that provided by reason and natural science. And put in that way, I think it's a highly plausible argument. Not conclusive--as various reviewers have pointed out, one can easily argue that post-Reformation developments, by no means determined by the Reformation, were more truly decisive than anything connected directly with Protestantism.

There's also a somewhat more nuanced way to put the argument than Gregory chooses, one that was made by Louis Bouyer in The Spirit and Forms of Protestantism. In this way of thinking, late medieval philosophy and theology tended to set up an either/or between God and creation. This became central to the Reformation. The Reformers sought to tear down human agency in order to exalt divine agency, rather than seeing the two as occupying radically different metaphysical "space" and thus as fundamentally compatible, as Aquinas did. (For instance, Aquinas seems to have no problems speaking of God causing humans to act in a particular way--freely. And yet he generally defines freedom in a "libertarian" rather than a "compatibilist" way, as the ability to choose one of two contraries.) Arguably, the Reformation's exaltation of the divine against the human caused Europeans to think of the two as a zero-sum game, so that every discovery of natural causality pushed God into a smaller and smaller "corner." Even this only makes sense if we speak in terms of a very general ethos rather than specific ideas about nature, since all the Reformers would have insisted that, in Calvin's words, nature is the "theater of God's glory," and would have agreed with the medieval tradition that God is active in and through "secondary causes." (Their opposition of divine and human causality was pretty much limited to soteriology and revelation, it seems to me.)

All of that being said, it's surely hard to deny that most modern people do have assumptions about God that are radically different from those of the patristic and medieval traditions. The popularity of "Intelligent Design" among conservative Christians, with the assumption that this says something meaningful about God's activity in creation, is one indication of this. (I wrote two blog posts about ID which you can read here and here.) As a number of people have pointed out, nearly everything that Richard Dawkins and other "New Atheists" write betrays a radical ignorance of what Christians have historically meant when we speak of God. It's incredibly hard to get through to atheists on this, not least because so many Christians hold precisely the view the atheists are attacking. To be sure, most medieval people weren't educated in the nuances of theology and no doubt held "crude" views of God, but the prevalence of misunderstandings (or just a radically different set of assumptions about what "God" means) among highly educated people indicates that there really is some kind of major chasm in the Western intellectual tradition. As MacIntyre famously said about ethics, there has been an intellectual eclipse similar to what post-apocalyptic sci-fi often posits with regard to science. And while the Reformation itself clearly did not cause the chasm, Gregory's thesis that it threw Europeans back on the resources of a purely abstract, non-theological concept of God seems plausible.

Plausible of course doesn't necessarily mean convincing. This is a highly interesting chapter, but not the strongest way to begin the book given the speculative nature of the argument and the serious reasons to question major parts of it. In later posts, I'll discuss whether the later chapters make stronger arguments (spoiler: generally speaking I believe they do).

Sunday, December 03, 2017

Silence

Several weeks ago, I finally watched Martin Scorsese's film Silence. Given the title and the theme, it's probably appropriate that it's taken me so long to write about it, though that's fairly typical for me.

For people who don't already know the film: it's based on a book by the Japanese novelist Shusako Endo, which is in turn based on historical events of the early 17th century during the Japanese persecution of Christians. A Portuguese Jesuit missionary, Christovao Ferreira, has disappeared in Japan, and rumor has it that he has apostasized. Two young priests are sent to find out what happened to him. After ministering to the persecuted Japanese Christians, they are betrayed and arrested. Both the novel and the film focus on one of them, a fictional character named Rodriguez (played by Andrew Garfield) who himself eventually follows Ferreira's footsteps and apostasizes.

The apostasy, in both book and film, is presented as a paradoxically Christian act. Rodriguez himself is never tortured--the Japanese authorities choose rather to torture Japanese Christians (who in some cases have already apostasized), telling Rodriguez that he can end their suffering by renouncing the faith himself. This is done by the ritual act of treading on a portrait of Christ, the "fumie." In the climax of the story, witnessing the tortures of the Japanese Christians, pressured by his own former mentor Ferreira with the argument that apostasy is the Christlike, unselfish thing to do, Rodriguez hears the voice of Christ saying, "You may trample. . . .it was to be trampled on by men that I was born into the world." His renunciation of Christ is therefore, an ultimate act of discipleship--or at least this is the suggestion that Endo's narrative makes, followed by Scorsese's film.

I read the novel many years ago and need to reread it. From here on, I will refer primarily to the film. In Scorsese's telling, at least, Rodriguez is fulfilling not only a Christian ideal (imitatio Christi) but a Buddhist one. Both Japanese interrogators and his apostate mentor Ferreira (played by Liam Neeson, himself a Buddhist in real life) suggest that by ceasing to cling to his faith, he would be letting go of self, transcending all attachments in an act of pure compassion. Scorsese explicitly endorsed this interpretation of Rodriguez' apostasy in an interview with him I heard on NPR. It isn't surprising, then, that many conservative Catholics have reacted badly to the film (as many Japanese Catholics reacted badly to Endo's original novel). Furthermore, Ferreira also tells Rodriguez that Christianity is fundamentally unsuited to Japan, like a tree that can't take root in a swamp. He argues that since the Japanese have no conception of a spiritual reality transcending the natural world, even the converts who suffer and die heroically for their faith are really dying for an unrecognizable distortion of Christianity and are acting primarily out of personal loyalty to Rodriguez and the other missionaries.

If I remember rightly, these ideas are present in the original novel. But as a viewer of the film, I find them unconvincing. Scorsese never shows us a good reason to believe that Ferreira is right. The actual glimpses we get of Japanese Christians seem to contradict his claim that they aren't "really" converts to Christianity and are simply motivated by loyalty to the missionaries. (And why are they so loyal to the missionaries anyway?) The Japanese elites who mastermind the persecution are sophisticated and plausible, but they have utter contempt for their own commoners and, of course, are willing to use horrifying brutality in order to preserve their social order. Ferreira's narrative, and that of his Japanese masters, appears to be self-serving nonsense given the evidence we see in the film. In fact, in the world of the film, the Japanese peasants receive Christianity with joy as a message that brings them hope and meaning, and they cling to it stubbornly in the face of agonizing torment.

The film actually ignores a great deal that could be said on behalf of the Japanese authorities and against seventeenth-century Catholicism. Except for one moment when the Japanese "Inquisitor" thinks Rodriguez is inviting Japan to "marry" the Portuguese (as he points out, he's actually talking about the Church), the imperialist undertones of the conflict aren't really addressed. The Japanese had good reason to worry about the way the Portuguese colonizers used Catholicism to give themselves a foothold. In Sri Lanka and Southern India, the Portuguese persecuted Buddhism, destroying the holiest relic of Sri Lankan Buddhism (Buddha's tooth) in a public ceremony (the Buddhists now claim that this was a replica and that the real tooth is still intact). Even the use of the term "Inquisitor" for the Japanese persecutor is ironic, given its normal association with Catholicism. Had Rodriguez gone back to Europe and proclaimed that Christ had told him to apostasize, he would have encountered his own religion's Inquisitors quite quickly. While the brutality of the Catholic Inquisition has often been exaggerated and in fact paled in comparison to the methods the Japanese used, the fact remains that the Catholics of this era were quite willing to use torture and execution to preserve their social order against threats. Similarly, early modern Europe was not exactly a place in which the lives and human dignity of peasants were highly regarded. Japan and Europe had a great deal in common, in fact. The film makes no attempt to draw out these parallels. That isn't a criticism--it's not as if the social injustices of early modern Europe or the violence employed on behalf of the Catholic Church are unknown in our culture, or as if Hollywood is generally interested in presenting an unduly favorable picture of Catholicism. But since some Catholics have apparently dismissed the film as anti-Catholic, it's worth noting that in many respects it is, if anything, the reverse. Indeed, it is if anything an anti-Buddhist film, shattering the "peaceful Buddhist" positive stereotype many in the West indulge in and showing the brutality of which a Buddhist culture was capable.

That is not to deny the very real sympathy Scorsese clearly feels with Buddhism. The Buddhist understanding of "no-self" and compassion comes through very clearly. But ironically, it is Rodriguez, not Ferreira, who most fully embodies it. Neeson's Ferreira is weary and sad, "empty" in the negative Western sense as well as (or instead of) the positive Buddhist one. In the flashbacks the film provides, it seems that his apostasy, unlike that of Rodriguez, was prompted by his own torture, after he had already witnessed that of others (Rodriguez, in contrast, is never harmed physically). His explanations seem like ex post facto rationalizations. But they give Rodriguez the framework on which he will act when the spectacle of the Japanese converts' torment becomes unbearable. Rodriguez does what Ferreira suggests, and he arguably fulfills the "selfless" ideal Ferreira has held out to him, but he does it for deeply Christian reasons. And in the end, Christianity gets the last word, with a final shot of Rodriguez corpse, wrapped in flames as part of a Buddhist funeral, clutching a crucifix.

Silence is an ambiguous and tragic film, not a work of propaganda for one side or the other. It defies easy explanations, even those of its own director. It captures the paradoxes and ambiguities of religious faith as powerfully as any film I have ever seen. And, precisely because of that, it is one of the most profoundly Christian films ever produced, worthy of a place just a step below the sublime Of Gods and Men.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)