(image: public domain)

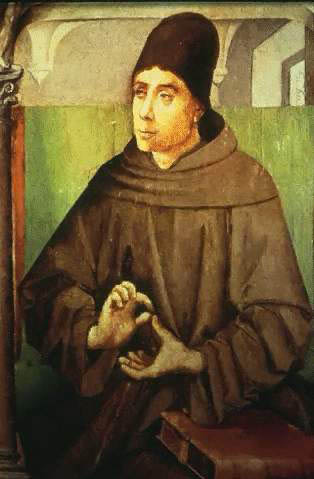

Chapter One of The Unintended Reformation is probably the most often cited. Indeed, many of the negative reactions to the book focus on the thesis Gregory argues here. Ironically, the chapter is atypical inasmuch as the root of modern secularism identified here lies not in the Reformation itself but in late medieval theology, specifically the work of Duns Scotus. According to Gregory, Scotus' concept of "univocity" radically altered the traditional Christian understanding of God. In traditional Christian theology (i.e., in the work of the Church Fathers, the Eastern tradition, or the earlier scholastics such as Aquinas), God is radically other than creation. All creation depends on God and participates in God, but no concept drawn from creation (as all our concepts are) is adequate to describe God. God is not a specific example of a broader category of "things that exist." God transcends all our categories and all our language. For Aquinas--himself much less "apophatic" (i.e., more willing to make positive claims about God) than many other great theologians of the tradition--even "being" can only be predicated of creatures and God analogously. Creaturely "being" derives from God's and thus has something that resembles it, but the differences are always going to be far greater than the similarities.

Scotus, in contrast, believes that there is a concept of "being" that can be univocally applied to God and creatures. Gregory argues that this is, implicitly, a radical move that makes it possible to think and speak about God in the same way we do about creation. But he admits that in itself this highly abstruse theory would have had little effect. This is where the Reformation comes in. By shattering the unity of Western Christendom and igniting fierce debates about how we know God's revelation, the Reformation cast Europeans back on an abstract, philosophical concept of God, which had been subtly altered by Scotus. Hence, post-Reformation Christians (both Catholic and Protestant) increasingly tended to think of God as the greatest of beings within a universe that could in principle be explained through reason and natural law. As the rapidly developing disciplines of the natural sciences explained more and more of reality without reference to God, God's place within this cosmos dwindled to that of the First Cause of Deism, and eventually to Feuerbach's mere projection of the human mind.

There is a reason why this sweeping argument has drawn so much criticism. In the first place, it's generally a bad idea to rest big claims about intellectual history on Scotus if you aren't a Scotus expert, because Scotus is such a darn difficult author. (In fact, I have a paper on Calvin I have wanted to publish for years which, among other revisions, probably needs to have all the Scotus cut out.) While Scotus did say that one can predicate being univocally of God and creatures, this was a very narrow and technical point, and the people I know who know something about Scotus generally seem to agree that it won't bear the weight Gregory puts on it. While Gregory does cite Scotus scholarship, he generally doesn't seem to be familiar with the bulk of recent work on Scotus, or at least he doesn't cite that work. Instead, his view seems to owe a lot to a 20th-century Catholic polemical trope of blaming the Reformation on the distortions of late medieval theology. In the 1990s, the largely Anglican theological movement called "Radical Orthodoxy" embraced the idea that Scotus had been the point where the Western theological tradition Went Wrong, and many more broadly "post-liberal" theologians of different traditions make similar points, it seems to me. Gregory cites Fr. (now Bishop) Robert Barron's 2007 The Priority of Christ for his view on the significance of Scotus' adoption of the concept of the univocity of being. Now I myself am very sympathetic to this strand of recent theology. I think there may be something to the "blame Scotus" argument, in fact. But it's unwise to rest too much weight on these claims when generally speaking the people who are actual Scotus experts qualify them at best and scoff at them at worst.

Furthermore, the idea that post-Scotus theologians, including the Protestant Reformers, thought of God as fundamentally the same kind of being we are seems very strange. William Ockham, seen by many (including Gregory) as taking Scotus' innovations even further, had a radically "apophatic" view of God in which God's nature is pretty much completely unknowable and all we can talk about is God's will. And this is generally the approach of the Reformers. Calvin, contrary to the stereotype many hold of him, fulminates against the idea that God is arbitrary, to the point of rejecting the basic distinction all medieval theologians made between what God has chosen to do and what God could have done but didn't. (I write about this in that paper I referred to earlier.) He believes that all God's actions flow from his nature. But the nature, again, is fundamentally unknowable. The older Catholic polemical trope of blaming everything on the late medieval scholastics, in fact, was more likely to argue that Ockham in particular made God so entirely other from us that reason has nothing to say about God--and this is certainly a more plausible interpretation of at least some of the early Protestant theologians (most notably Luther).

But even if Gregory is all out to sea on what he says about Scotus, and wrong to suggest that the Reformers followed Scotus in this respect, that doesn't really affect the basic argument of the chapter, at least insofar as it supports the overall case made by the book. After all, blaming Scotus wouldn't, in itself, support Gregory's argument that the Reformation is the source of the modern secular world. Rather, Gregory's most significant argument is that the sharp disagreements about God's acts of revelation that took place in the Reformation left post-Reformation Christians with no sure ground to speak about God except that provided by reason and natural science. And put in that way, I think it's a highly plausible argument. Not conclusive--as various reviewers have pointed out, one can easily argue that post-Reformation developments, by no means determined by the Reformation, were more truly decisive than anything connected directly with Protestantism.

There's also a somewhat more nuanced way to put the argument than Gregory chooses, one that was made by Louis Bouyer in The Spirit and Forms of Protestantism. In this way of thinking, late medieval philosophy and theology tended to set up an either/or between God and creation. This became central to the Reformation. The Reformers sought to tear down human agency in order to exalt divine agency, rather than seeing the two as occupying radically different metaphysical "space" and thus as fundamentally compatible, as Aquinas did. (For instance, Aquinas seems to have no problems speaking of God causing humans to act in a particular way--freely. And yet he generally defines freedom in a "libertarian" rather than a "compatibilist" way, as the ability to choose one of two contraries.) Arguably, the Reformation's exaltation of the divine against the human caused Europeans to think of the two as a zero-sum game, so that every discovery of natural causality pushed God into a smaller and smaller "corner." Even this only makes sense if we speak in terms of a very general ethos rather than specific ideas about nature, since all the Reformers would have insisted that, in Calvin's words, nature is the "theater of God's glory," and would have agreed with the medieval tradition that God is active in and through "secondary causes." (Their opposition of divine and human causality was pretty much limited to soteriology and revelation, it seems to me.)

All of that being said, it's surely hard to deny that most modern people do have assumptions about God that are radically different from those of the patristic and medieval traditions. The popularity of "Intelligent Design" among conservative Christians, with the assumption that this says something meaningful about God's activity in creation, is one indication of this. (I wrote two blog posts about ID which you can read here and here.) As a number of people have pointed out, nearly everything that Richard Dawkins and other "New Atheists" write betrays a radical ignorance of what Christians have historically meant when we speak of God. It's incredibly hard to get through to atheists on this, not least because so many Christians hold precisely the view the atheists are attacking. To be sure, most medieval people weren't educated in the nuances of theology and no doubt held "crude" views of God, but the prevalence of misunderstandings (or just a radically different set of assumptions about what "God" means) among highly educated people indicates that there really is some kind of major chasm in the Western intellectual tradition. As MacIntyre famously said about ethics, there has been an intellectual eclipse similar to what post-apocalyptic sci-fi often posits with regard to science. And while the Reformation itself clearly did not cause the chasm, Gregory's thesis that it threw Europeans back on the resources of a purely abstract, non-theological concept of God seems plausible.

Plausible of course doesn't necessarily mean convincing. This is a highly interesting chapter, but not the strongest way to begin the book given the speculative nature of the argument and the serious reasons to question major parts of it. In later posts, I'll discuss whether the later chapters make stronger arguments (spoiler: generally speaking I believe they do).

No comments:

Post a Comment